Tax Basics

From Capital Gains Tax to Franking Credits, learn how tax works in the stock market

Key Concepts

- Capital gains tax (CGT) applies whenever you sell a stock.

- Capital gains and losses over the financial year are added together to get your net capital gain or loss. Capital losses can be carried forward to offset any capital gains in future tax years.

- Capital gains tax can be reduced by holding stocks for longer than 12 months (depending on the country).

- Dividends are classified as income and tax at your personal marginal tax rate.

- In Australia, companies pay franking credits that act to offset your income tax.

Tax

Tax is an important consideration in investing that is often overlooked by new investors. Money made in stocks is not free, and tax implications can have a material impact on your returns. There are also various discounts and benefits available which you can take advantage of to boost your returns.

Here we will discuss the general concepts of tax that you should be aware of. However, tax law changes over time and is different in every country, so the information provided should not be formally relied upon. You should make sure to become accustomed to the tax law of your own country.

The amount of tax you pay is calculated on your taxable income which is the money you earned during the financial year from all sources, including your salary and investment gains, less allowable deductions. Your taxable income will determine which tax bracket you fall into. Each tax bracket has its own marginal tax rate, which is how much tax you pay on each additional dollar earned.

Tax is calculated and payable at the end of the Financial Year. In Australia, the Financial Year runs from July to June. It is important to be aware of the tax liabilities incurred by your investments so that you are not surprised by an abnormally large tax bill at the end of the financial year.

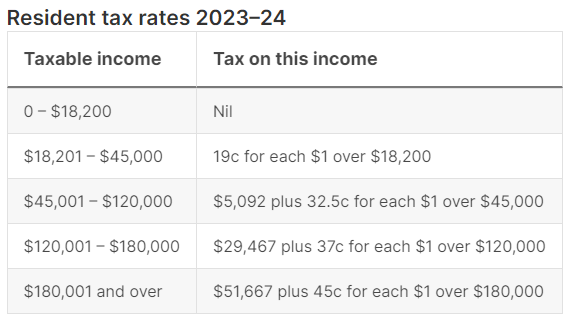

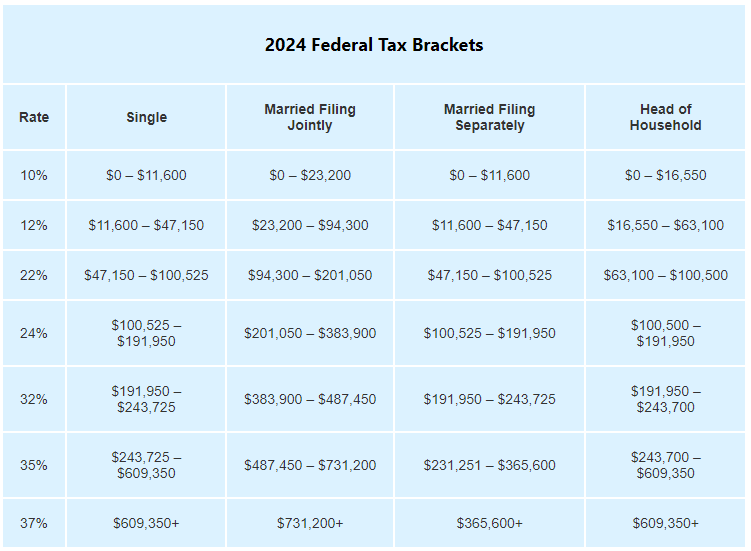

Below are the marginal tax systems from Australia and the United States at the time of writing. I recommend finding out what your personal marginal tax rate is to provide context for the rest of this section and inform some of the important decisions you will have to make on your investing journey.

You can use the Australian Tax Office's Simple Tax Calculator to estimate your tax liability for any previous financial year.

|  |

| Australian resident tax rates for 2023-24 | United States resident tax rates for 2024 |

Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

When you sell a stock for more than you bought it, the profit you make is called a capital gain. If instead you sell a stock for less than you bought, it is called a capital loss. The capital gains and losses accross all your investments are added together to get your net capital gain. If the resulting figure is positive it is added to your taxable income and you will pay tax on it.

This means that if you make a large capital gain on one stock, you can pay less tax at the end of the financial year by selling another stock at a loss. This strategy is called tax loss harvesting.

If your net capital gain is negative (also known as net capital loss) at the end of the financial year, the amount can be carried forward to be offset against any capital gains in future years. This means that the tax benefit of selling stocks at a loss is not lost if you do not have any gains to offset it with.

This can provide incentive to sell stocks that you have lost money on. Many investors can be reluctant to do this. It is important to remain objective in these situations. On one hand, you can lock in a tangible benefit by offsetting the loss against your net capital gain, or you could hope the stock recovers by more than the value of this benefit in order to justify not selling it. This is a tradeoff that you must assess yourself.

In some countries, like the US and Australia, capital gains are taxed differently for investments held for longer than 12 months. In the US, long-term capital gains are taxed a reduced rate between 0% and 20%. In Australia, long-term capital gains incur a 50% tax discount.

These discounts are material, and should be kept in mind when deciding to sell an investment. Let's look at an example. Say you are an Australian resident and you are currently profitting $1,000 on a stock that you have held for 11 months. Assume your marginal tax rate is 19%. If you sell the stock now, you will incur a Capital Gains Tax of $190 and will get to keep $810 of your profit. On the other hand, if you wait for one more month and sell once you have held the stock for the full 12 months, a discount of 50% will apply and you will only incur a Capital Gains Tax of $95. Your profit after tax will has jumped from $810 to $905 if you hold it for just one more month.

This means that for stocks that you have nearly held for 12 months, it is often better to delay the decision to sell them in order to receive the CGT discount. The significance of this discount increases with both the size of your profit and your marginal tax rate. However, this is assumes that the stocks in question will not fall significantly in value between now and that 12 months milestone. You must assess this risk for yourself and determine whether the tax saving is meaningful enough to continue holding the stocks in question.

Capital gains tax can be reduced by holding stocks for longer than 12 months (depending on the country).

Cost Basis

What happens to your CGT if you buy the same stock more than once? Your capital gains tax calculation is not as simple.

This is where the concept of a cost basis comes in. Your cost basis the total cost incurred to purchase your shares, plus any related transactions like brokerage or reinvested divends. An equivalent way of thinking about it is as the average purchase price multiplied by the number of shares. When you eventually sell your shares, the sale price is compared to this cost basis to calculate your capital gains tax.

If I purchase 10 shares of a stock for $100 today, and 10 shares of that same stock for $120 tomorrow, my cost basis would be $220 or $11 per share. If I get lucky and sell all 20 shares for $240 my capital gain would be $240 - $220 = $20.

What if you don't sell all your shares at the same time? The typical method in this situation is called first-in, first-out (FIFO). This method applies the purchase price of the first shares you bought. In the above example, if I sold 10 of my 20 shares at the same price my capital gain would be $120 - $100 (the price of my first purchase) = $20. That first purchase then get removes from my cost basis, which would then be $120 or $12 per share.

Dividends

Dividends, being your other source of income from investing in stocks, are also subject to tax. The tax treatment of dividends is very straightforward. The amount of the dividend is simply added to your taxable income and taxed at your marginal tax rate.

Another way you can receive dividends in through a Dividend Reinvestment Plan or DRP. Under a DRP, the dividend is paid through additional shares instead of cash.

The tax on a dividend reinvestment plan is the same as if you receive the dividend in cash. The additional shares are said to be acquired at the market price of the shares at the time of the dividend, and your cost basis will increase accordingly.

Franking or Imputation Credits

Australia has a special system for taxing dividends, called the imputation tax system. Under this system, Australian resident shareholders can receive a special credit called a franking credit with their dividends to offset their tax liability. The franking credit represents the amount in income tax that has already been paid by the company on its earnings.

The purpose of the imputation tax system is to eliminate double-taxation of corporate earnings. In classical tax systems, like in the US, money that the company earns is taxed once by the company itself and then again when it is received by the shareholder as a dividend.

Income tax paid by Australian companies is treated like a "pre-payment" of tax on behalf of its shareholders. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO), awards companies with franking credits equivalent to the amount of tax paid. Companies can then pass these onto their shareholders, who can redeem them with the ATO to offset their personal tax liability.

Franking credits can be thought of as a voucher that says "this amount of tax has already been paid".

The ratio of the franking credit to the tax paid on the dividend is called the franking amount, and is not always 100%. Some ASX-listed companies don't generate 100% of their earnings within Australia, meaning they will not receive franking credits for the portion of their earnings generated overseas. The company can also hold onto their franking credits as long as they like before choosing to pay them to shareholders.

Let's walkthrough an example. A company earns $1,000 in income and pays $300 in income tax (the corporate tax rate in Australia is 30%). It decides to return 100% of its income to its only shareholder via a dividend. The shareholder receives the $700 dividend plus a franking credit of $300, equivalent to the tax paid by the company. The gross amount received by the shareholder is the value of the dividend plus the franking credit or $1,000. Assuming the shareholder's marginal If the shareholder's tax rate is 19%, the tax payable on the dividend is $190. Now we apply the franking credit, which was $300. Because the franking credit is greater than the tax payable, the shareholder receive a tax refund of $300 - $190 = $110. The net income to the shareholder is then $700 + $110 = $810.

If the shareholder's marginal tax rate is instead larger than 30% the shareholder won't receive a refund, but will have the tax payable reduced by the amount of the franking credit.

Use the calculator below to see how marginal tax rate and the franking amount affect income.

Imputation Tax Calculator

This article is intended for educational purposes only. The information provided is general in nature and does not consider your personal financial circumstances. Please consult a certified financial advisor if you require advice.